| Tao River Archaeological Project (TRAP) | |

TRAP Geophysics training workshop at the Dayatou Site (Guanghe and Lintao Counties, Gansu) - June 2015 | The Tao River Archaeological Project investigates technological changes in Northwest China around 4000 years ago. At that time, a series of changes in subsistence and craft technologies conspired to radically transform material culture and human lives along the “proto-Silk Road” in Northwest China. The most significant changes occurred during the Qijia Culture period (ca. 4200-3600 calBP). Bronze metallurgy became increasingly important, ceramic technology underwent radical changes, and new crops and animals moved in from the west and north. These changes laid the foundation for the Chinese Bronze Age, however the specific natures of these technological changes remain obscure. Who were the people involved in establishing or generating new technological practices? Were the changes widespread or limited to certain places and times? Do technological changes relate to population movement? Do changes coincide with significant environmental changes? In particular, we lack an understanding of (1) the degree to which technologies changed at the same time within local areas of the broader region of Northwest China before, during, and after the Qijia period itself, (2) the precise chronology of specific manifestations of subsistence and craft technologies and the degree to which change was rapid or gradual, (3) the nature of the environment surrounding specific examples of technological persistence or change in this region, and (4) whether technologies used in widely published burial practices differ significantly from those evident at unexplored residential locations. The Tao River Archaeological Project (TRAP) Investigates these questions through survey, geophysics, and excavation at known sites in the Tao River focusing on settlements that can be attributed to the Majiayao, Banshan, Machang, Qijia, Xindian and Siwa cultural traditions of the region. Preliminary work began in 2012, and excavations commenced in 2016, starting at the site of Qijiaping. TRAP has run two capacity building training programs during the preliminary phases of research. The first was a geophysics training program directed by Dr. Timothy Horsley and the second was a GIS training program at the Gansu Provincial Institute of Archaeology, both in June 2015. |

| Oracle Bone Database Project | |

| Oracle bones—animal bones used for pyro-osteomantic divination rituals in East Asia—are one of the most important types of bone artifacts in Chinese Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeological sites and the source of inscriptions containing the earliest writing in ancient China. Although these inscriptions are the focus of most research, oracle bone use far pre-dates the inscribed examples and continues after they were a primary medium for writing. Previous research indicates that standardization and specialization of oracle bone divination occurred leading up to the Shang Dynasty when oracle bones became part of elaborate ritual practices that were critical to state power. This research is based on non-systematic data and it is unclear whether the limited published examples accurately represent the temporal and geographic trends in oracle bone divination. The Oracle Bone Project is a three year project to study the origins of oracle bone divination rituals, their spread across Asia during the Neolithic, and the ultimate development of oracle bone divination as a central part of Shang royal religious practices. The joint US-China project will involve five components: 1) data collection from oracle bones housed at storage facilities in China; 2) laboratory analysis including experimental reproduction of oracle bone manufacturing techniques, microscopic analysis of tool marks on oracle bones, and ancient DNA analysis of oracle bones from the Shang capital at Anyang; 3) creation of an oracle bone database on the open access data publishing site Open Context (opencontext.org); 4) long-term database expansion to include additional sites and regions both inside and outside of China; and 5) data analysis to examine spatial and temporal trends in oracle bone use in East Asia. |

Zhongba: Salt Production, Specialization, and Interregional Interaction | |

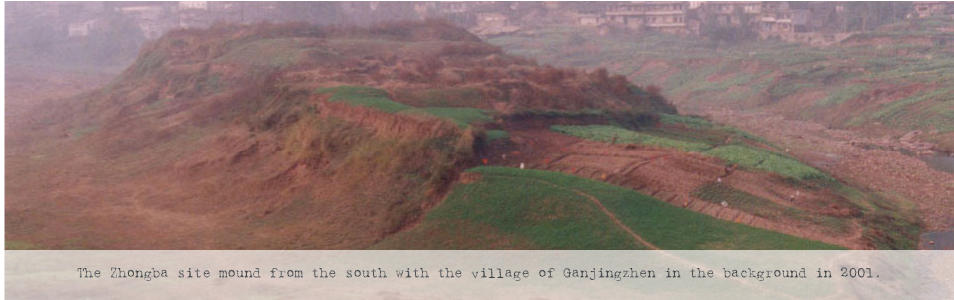

| Starting in 1999, I joined a research project at the site of Zhongba in Zhong Xian County, Chongqing Municipality. At the time we hypothesized that the site was a possible location for specialized salt production dating to periods earlier than the known evidence for salt production in China. Our investigations at the site demonstrated that salt production was, in fact, a major activity at the site (Flad et al. 2005[1]). My research was not, however confined to this narrow question. Instead, I became interested in how the remains we were excavating at Zhongba related to significant issues in economic anthropology. Specifically, I have explored how salt production remains from the Zhongba workshop can be used to examine the nature of “specialization” at the site. I argued in my dissertation, an in two essays in a book I edited (Flad and Hruby 2007; Flad 2007), that standard models used by archaeologists are not entirely appropriate for understanding the manufacture of products like salt, which cannot be easily categorized into ontological types. The research at Zhongba speaks not only to production, but also to issues of trade and interregional interaction. This topic was the focus of a seminar I lead in the department of Anthropology during my second year at Harvard (Anthropology 2290) and is a principle focus of a book I am currently writing with a former classmate (Prof. Pochan Chen of National Taiwan University) titled Ancient Central China, which is under contract with University of Cambridge Press. This book, which is a synthetic treatment of the late Neolithic and Bronze Age of the Sichuan Basin, the Three Gorges, and the Middle Yangzi River valley, argues that politically peripheral regions such as the Three Gorges (where Zhongba is located) can be central to economic landscapes and are not best understood as regions that are best explained from the perspective of political cores (as some perspectives, such as World Systems Theory, would do). Both production and trade are topics that are integral to economic anthropology, which remains a sub-field within the study of complex society that I take interest in (see, for example, my article on the concept of “value” as it applies to Xinglongwa jades - Flad 2006) Various aspects of my work on Zhongba have been the focus of many of my publications. I have published analyses of the animal bones from the site, which I argue were primarily the remains of meat and fish salting activities (Flad 2005; Flad and Yuan 2006). I have analyzed and discussed the radiocarbon dates from the site and their significance in understanding technological change in the region (Flad et al. 2009; Wu et al. 2007). I have also helped with the translation and editing of a series of books on salt archaeology in China (Li and Falkenhausen 2006), volume 3 of which will contain many essays on Zhongba. Much of this research has been presented at international conferences and workshops and is collected in my recent book: Salt Production and Social Hierarchy in Ancient China, published by Cambridge University Press. |

| Chengdu Plain Archaeological Survey: Emerging Complexity and the Archaeology of Landscape | |

Auger survey during the 2008-09 CPAS field season.  Results from auger and surface surveys from the Chengdu Plain Archaeological Survey 2005-2009. | Since completing my Ph.D., I have been involved in a new survey project focused on the beginnings of sedentary society and the emergence of social complexity in the Chengdu Plain of Sichuan Province. This survey involves a novel use of multiple survey strategies in concert in order to address the complex environment of the Chengdu Plain. Due to the problems posed by paddy-field rice agriculture and poor ground visibility we combine several different procedures (field-walking, auger survey, remote sensing, and geomorphology) to reconstruct the ancient landscape. The project has brought together scholars from several Chinese institutions (Peking University; Chengdu City Institute of Archaeology; and the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences), several American Institutions (Harvard; UCLA; Washington University in St. Louis) and others (National Taiwan University; University College of London). I have been responsible for coordinating research in the field and directing the auger survey and have been principally in charge of the overall management of data from the project in an integrated GIS (Geographical Information System) database. The project is focused on several critical issues. First, we wish to examine whether the complex polities that emerged at the end of the second millennium BC in the Sichuan Basin (as evidenced by the famous site of Sanxingdui) were indigenous developments in the region or the result of imposition from the outside. The nature of developing complexity in the region has significant implications for the big picture of how “civilization” emerged in East Asia. Second, we are interested in the process by which rice agriculture spread to regions outside its initial core. The Sichuan Basin is a perfect example of the secondary adoption of agriculture where we can explore the relationship between changes in subsistence and emerging complexity. Two articles on the two preliminary seasons of this project have been published in Nanfang minzu kaogu [Southern Archaeology and Ethnology], Vol. 6. I have presented our methodologies and preliminary results widely at guest lectures at several American universities and international conferences. The project has been funded by support from the American Philosophical Society, the Harvard University Asia Center, the American School of Prehistoric Research, the Department of Anthropology at Harvard, the Luce Foundation and the Wenner Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. We concluded field research in 2011 and are currently working on a bilingual report of the project results. |

Human-Animal Interaction: Synthesizing Chinese Zooarchaeological Research | |

Turtle plastron used in pyromantic divination from the site of Zhongba. | Another focus of my research has been studying the ways that animal exploitation was connected to aspects of social complexity in ancient China. I have explored this topic through a number of different angles. In the context of the Zhongba project, my research on zooarchaeological remains and the production of salted meat and fish products explores how animal products were integral to interregional interaction (Flad 2005). This study led me to examine zooarchaeology in China more widely, and other aspects of human-animal interactions that relate to social complexity. One example is the topic of domestication, and together with Prof. Yuan Jing, the director of the scientific laboratories of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Institute of Archaeology, I have written several papers that synthesize published data about early evidence for this process (Flad et al. 2007; Yuan and Flad 2002, 2003, 2005). Animal domestication is a crucial process in human history as it marks a radical change in one aspect of subsistence practice and relates to issues of scheduling, community integration, and specialization. I have also been interested in the use of animals in rituals, and have published papers related to this topic (eg. Yuan and Flad 2008, Flad 2008). This topic is the focus of an ongoing collaboration with LI Zhipeng of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology to catalog the variation in pyromantic divination (oracle bones) throughout Chinese prehistory and early historical periods. (See Oracle Bone Database Project) |

Complex Societies During the Second Millennium on the Northern Frontier | |

The Siba culture site of Donghuishan in Minle, Gansu in 2005.  Rowan Flad conducting baulk cleaning and soil sampling at Donghuishan in 2005. | My interest in second millennium BC complex societies extends to various regions of the People’s Republic of China. Two sites to the north of the Central Plains are of particular interest: The Lower Xiajiadian culture site of Dadianzi in Aohan Banner, Inner Mongolia to the Northeast, and the Siba culture of Donghuishan in the Hexi Corridor of Gansu to the Northwest. Both have been the focus of extensive excavations of cemeteries, but little work has been done on the associated settlements. I have published an evaluation of the cemetery data from Dadianzi as a study in examining the ritual aspects of burial practices (Flad 1998, 2001). In 2008 I visited the site with Dr. LIU Guoxiang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology to examine the landscape context of this settlement. The roughly contemporary site of Donghuishan in Minle, Gansu is an important site because of the early dates attributed to wheat remains found at the site. We have published the results from that research (Flad et al. 2010), and I am currently in discussions with the Gansu Provincial Institute of Archaeology to begin a research project in Southern Gansu that will connect this research to the work we have been conducting in Sichuan. That project will explore the crucial time period between ca. 2500-1500 BC by examining sites associated with the Majiayao, Banshan, Machang, Qijia, and Xindian cultures. |