“‘Peace is for the Strong, War is for the Weak’: The Congress of Vienna as an Instrument of Power”

Stella Ghervas, CES Harvard University; MSHA, Bordeaux

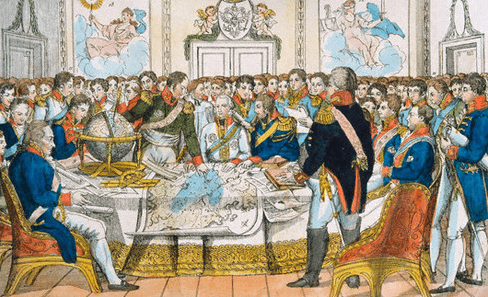

The Congress of Vienna (1814-15) was marked by an outstanding innovation: Russia, Britain, Austria and Prussia consciously established an international system based on active cooperation, ushering in a period of relative stability in Europe. The great powers, spurred by Tsar Alexander I, made it an explicit policy to maintain peace at all costs. In doing so, they attempted to give up the system of the balance of power, effectively banning war among themselves for nearly four decades, until the outbreak of the Crimean War (1853). The effects of their innovation extended in the longue durée, since the Concert of Europe continued until the outbreak of WWI in 1914, and its legacy can be felt to this day. What were the ideal and practical motivations of such a system? From our horizon of experience, can we explain why it was attempted at that time and not before, in the eighteenth century? Similarly, why did it function for so long and what factors led to its collapse? The policy conducted by the great powers in the post-Napoleonic era makes for fascinating reading, because it regarded peace as an expression of power and strength.

“Recasting Central Europe: ‘Hard’ and ‘Soft Power’ at the Congress of Vienna”

Mark Jarrett, Author of “The Congress of Vienna and its Legacy”

The territorial settlement of 1815 has been widely hailed as the foundation upon which the peace of early nineteenth-century Europe rested. But when the powers gathered in September 1814, the contours of that settlement were far from clear. The key issue was the Tsar’s plan to reconstruct Central Europe by creating a new Polish Kingdom under Russian tutelage and transferring the independent Kingdom of Saxony to Prussia as compensation. Lord Castlereagh and Prince Metternich, the British and Austrian plenipotentiaries, were adamantly opposed to this scheme. For two centuries, historians have debated how serious was this confrontation and whether it could have actually led to an outbreak of war between the allied victors over Napoleon. What factors led to the successful resolution of this dispute? In particular, what was the role of the Secret Treaty of 3 January 1815? And does Joseph Nye’s concept of “hard” and “soft power” help to illuminate the outcome?

“From London and Lübeck to Geneva and Algiers: Abolition of the Slave Trade and Barbary Captivity at the Congress of Vienna”

Brian Vick, Emory University

Often deemed a turning point or moment of “transformation” for European international relations, the Congress of Vienna saw both the creation of new types of collective security arrangements and a trend towards humanitarian intervention on behalf of groups threatened with attacks on their rights and freedom, not only in Europe but in the world beyond. The talk explores the origins of these changes at the Vienna Congress and shows how they can only be fully understood within the framework of a new way of defining power politics and studying diplomacy. In particular the talk focuses on the movements to internationalize the abolition of the African slave trade and to interdict the taking of European captives by Barbary corsairs. These efforts, like the other Congress negotiations, involved an intricate interplay of political actors at the multiple levels of royal courts, governments, and broader publics, in cabinets and festivities as well as in salons and the press.

“Sexual Congress: Women, Intimacy and ‘International’ Politics in Vienna, 1814-1815”

Glenda Sluga, Sydney University (via videoconference)

As often as the history of the Congress of Vienna has been told as an international story of male statesmen and sovereigns constructing the Concert of Europe, it has been spread as an entertainingly salacious tale of the “dancing congress”. Women only appear in this latter version, as emblems of a pre-professional conferencing system that contrasts with the modern “scientific” forms of diplomacy and international political processes inaugurated by the Congress. This paper brings together the two versions of the Congress in order to reconsider the nature of international politics and power in Europe over this period, and its intersecting private and public dimensions. It takes as its point of departure the observation made by the Austrian historian Hilde Spiel in the 1960s, that never before or after had “a group of statesmen and politicians, assembled solely and exclusively to deal with matters of commonweal interest, labored so extensively and decisively under the influence of women”. How should we understand the simultaneous presence and absence of women in the history of international politics? Taking as its focus the Duchess of Sagan and Princess Bagration—two women whose activities and homes were of particular interest to the Austrian secret police—this paper tracks continuities in the modern history of diplomacy before and after 1815, the ideological work that took place during the congress to delimit women’s roles, and the shifting gendered social register that came to define a new era of international relations.