Cambridge, Mass.—As many readers will know, I have been studying Hinduism for over 40 years, since I first visited Kathmandu, Nepal, in 1973, to teach at St. Xavier’s School. Over the years, people have asked me what difference this study has made for me. I have always had to give a complicated answer: “not much, and everything.” I live here, in the United States, not in Nepal or India, and at best am a missionary in reverse, bringing Hinduism to the attention of American Christians; I have not become a Hindu, I am still a Catholic priest and a Jesuit; I am not a pluralist who believes that all religions are varying affirmations of the same truth, I prefer to go deep in my own tradition to interpret pluralism; I am a Catholic theologian, just a slightly different kind. People sometime persist: How then has Hinduism made a difference in my practice of Catholicism, as a priest? Often enough, I add that I almost never mention India or Hinduism in my homilies in my Sunday parish (where I’ve helped for over 19 years) – but that my study of Hinduism has changed how I preach, what I am looking for and what I find in the readings of any given day. It is hard to explain how this works out – to be deeply influenced by Hinduism in preparing my homilies, while yet almost never mentioning Hinduism from the pulpit.

But I found today that my reading of the Gospel deeply resonated with my study of Hinduism, and that it perhaps serves as a good example. Let me explain this by several general observations and then several particular comments on the Gospel read in church today, the ten lepers.

On the general level: First, I think it quite in keeping with Hindu tradition that I never mention Hinduism from the pulpit: the point is to address people where they are, in the tradition where they belong, without disturbing them by complicated new information. One finds God where one is, not by going somewhere else. So why would I preach on Hinduism, to Catholics? Simply explain the words of the Bible to Catholics, that is enough. If one preaches to Hindus, I suppose, words from a Hindu scripture would be enough. Second, Hindu teachers tend to read texts without much reference to historical context or to current events: they dwell in the story at hand, and bring its details to life. I am not much of a story-teller anyway, I am sure, but I am always content likewise simply to go inside the readings of the day, letting the words roll over me, so to speak, to become, for the moment, all that matters: in Greek, which I can check, and with a sense of the Hebrew that I must pick up from checking others’ translations. So one goes deep inside a Gospel passage, for instance, and sees what one finds. This is all the matters for speaker and listeners on a Sunday morning. Third, sacred texts are texts; the ideas may be fine, but the transformative power of the text lies in each and every word, so one must read very closely and carefully. All one needs to do is help us all to really hear the words. To preach well, depends a lot simply on reading slowly and attentively; Hindu teachers too often simply go over a text, word by word.

I had pondered today’s simple Gospel all week long:

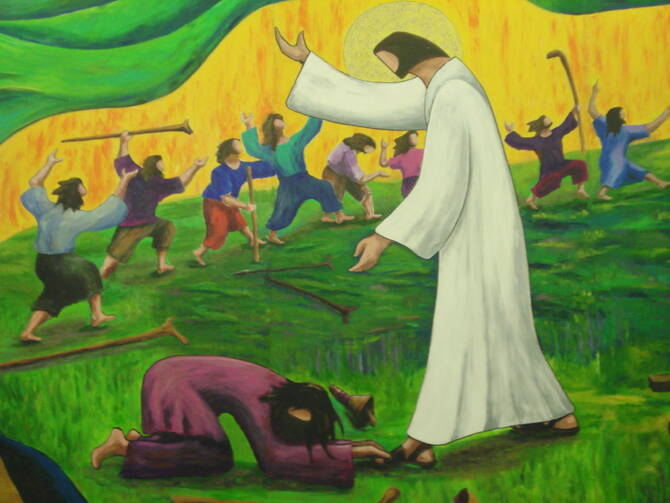

On the way to Jerusalem Jesus was going through the region between Samaria and Galilee. As he entered a village, ten lepers approached him. Keeping their distance, they called out, saying, ‘Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!’ When he saw them, he said to them, ‘Go and show yourselves to the priests.’ And as they went, they were made clean. Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice. He prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him. And he was a Samaritan. Then Jesus asked, ‘Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they? none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?’ Then he said to him, ‘Get up and go on your way; Was your faith has made you well.’ (Luke 17:11-19)

Having read so many Hindu texts, my expectation usually is that the message is in the details. So with my congregation, I began with a question: Why does Jesus send them on their way to the priests before he heals them? We may be misled, by the end of the passage, into thinking that only the Samaritan had faith. Yet all ten were people of faith, willing to expose themselves and risk everything by going to the priests, even unclean: obey, even when there are no visible reasons to. It was only on the road that they were cleansed of their disease. Their faith came first, before any signs of a cure.

Given my interreligious learning, I am also alert to the danger of making one religion look good at the expense of another: so even here, there is no point in making it seem as if Jews are ungrateful and the Samaritan leper the example of gratitude. All ten risked everything in going to the priests; the nine Jewish lepers (if they were all Jewish) were obeying the command of Jesus, to go first to the priests. Obedience too is a virtue. It could hardly be surprising that a Samaritan leper would be the one to consider that encounter with the priests less important—the priests are presumably Jewish, and he is not: what does he have to lose, in turning back? This is not a Gospel that makes Jews look bad and Samaritans look good. I have known too many Hindus to want to make one religion look good, merely at the expense of another.

But what then is special about this tenth leper? He praises God on the way back, and might just as well have praised God on his way home to Samaria. So why is he special? It is here that a Hindu instinct comes to the fore, since anyone who has studied Hinduism will immediately resonate with what the Samaritan actually does: “He prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him.” Thanks yes, but in the posture of surrender, prostration, jumps out as the perfect gesture: for it is there, where Jesus is, that the healing actually took place. To be at the feet of the Lord Jesus, a Hindu teacher will tell us, is the perfect place to be, the highest goal in life. This is a superlative act of great love that any Hindu would recognize.

It is also a sacramental moment: the words are not enough, praising God is not enough, nor even thanking Jesus “keeping his distance” as at the start of the story. “Here and now” too would resonate with most Hindu readers. And so, in my homily, I detoured briefly to the first reading from 2 Kings, where Elijah cures Naaman, commander of the army of the king of Aram. I went there not because of the leprosy, surely the intention of those compiling the Sunday readings, but because of what Naaman wants as he leaves:

Then Naaman said, ‘If not, please let two mule-loads of earth be given to your servant; for your servant will no longer offer burnt-offering or sacrifice to any god except the Lord. (2 Kings 5:17)

Two mule-loads of earth: it is hard to imagine being more material, physical, local, than this: Naaman wants the very soil of Israel, that he might stand of it for his prayer: not just to thank God, or praise the God of Israel, but in a rather primal fashion, to abide on the soil of Israel for his worship. This too—an idea with Biblical roots, to be sure—makes perfect sense in light of my understanding of Hinduism: God here and now, such that one can prostrate before God, and in a holy place, on sacred ground, because God was here. God, who is everywhere, is especially present in some holy places. Both Catholics and Hindus appreciate material, holy, tangible things.

Such was the substance of my reading of the text. Readers may observe that there is no proof here, no claims about the influence of Hinduism on the Bible, and no claim about a reading of the Gospel that could not have happened otherwise. All this is true. But my point is more subtle: what I noticed and noted in the Gospel both moved away from the theme of “thanksgiving”—but later returned to it in a heightened fashion. I became sensitive to certain odd dynamics—the command to go to the priests before the cure occurred, the praise of the Samaritan who had no real reason to go to the priests and who easily turn back, and the event of his prostration—because I have read so many Hindu texts that resonate with such turns and eventualities.

Still, of course, one might expect more, if one wishes for a Hindu reading of a Gospel. But there is more power, that goes deeper and lasts longer, in the subtle and simple. I doubt if I would have noticed what I did in the Gospel, without my study of Hinduism. That study has brought out the power of this tale of thanksgiving as utter devotion, here and now. And that is the point: studying another religion helps us to find in our own what we would not have ever noticed there.