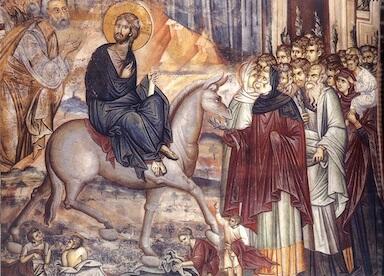

Jesus’ final entry into Jerusalem, the signal event remembered on Palm Sunday, is an indelible part of the narrative of Holy Week, which begins with a kind of triumph and ends in a kind of disaster. We cannot but contrast how the crowds react at the beginning of the week,

Jesus’ final entry into Jerusalem, the signal event remembered on Palm Sunday, is an indelible part of the narrative of Holy Week, which begins with a kind of triumph and ends in a kind of disaster. We cannot but contrast how the crowds react at the beginning of the week,

"Then they brought the colt to Jesus and threw their cloaks on it; and he sat on it. Many people spread their cloaks on the road, and others spread leafy branches that they had cut in the fields. Then those who went ahead and those who followed were shouting, “Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed is the coming kingdom of our ancestor David! Hosanna in the highest heaven!” (Mark 11.7-10)

and how they react at the week’s end,

“Do you want me to release to you the king of the Jews?” asked Pilate, knowing it was out of self-interest that the chief priests had handed Jesus over to him. But the chief priests stirred up the crowd to have Pilate release Barabbas instead. “What shall I do, then, with the one you call the king of the Jews?” Pilate asked them. “Crucify him!” they shouted. “Why? What crime has he committed?” asked Pilate. But they shouted all the louder, “Crucify him!” Wanting to satisfy the crowd, Pilate released Barabbas to them. He had Jesus flogged, and handed him over to be crucified. (15.9-15)

Such a contrast within one week! We do not know for certain that it was the same crowd which cheered and jeered, even if the likelihood is there. But surely we must share Pilate’s question: Why, indeed? What crime has he committed?" We can blame the general plight of human fickleness, human hard-heartedness, but that is too generic. As usual Mark wants us to look deeper still. Mark 11 gives us a few clues as to what is really at stake, and for that we should look beyond the Palm Sunday scene we so vividly remember.

First, note that the entrance into the city does not end as gloriously as some surely would have expected. Jesus does not take over the Temple, drive out the Romans, or unseat Herod. Rather, the ending is an anticlimax:

"Jesus entered Jerusalem and went into the Temple courts. He looked around at everything, but since it was already late, he went out to Bethany with the Twelve. (11.11)

Perhaps Jerusalem and the Temple are not his destiny after all? So what is this Jesus up to? For this, note the scenes that follow in Mark 11 (passages never read in Holy Week), since they give a twist to the whole story. First, and very oddly, Jesus curses an innocent fig tree for not being ready for his visit:

"The next day as they were leaving Bethany, Jesus was hungry. Seeing in the distance a fig tree in leaf, he went to find out if it had any fruit. When he reached it, he found nothing but leaves, because it was not the season for figs. But he said to the tree, “May no one ever eat fruit from you again!” (11.12-14)

Why, if it is not the season for figs? And why mention the incident at all? No reason is given and then suddenly the scene shifts, as Jesus empties the Temple, which too was not ready for his visit:

Why, if it is not the season for figs? And why mention the incident at all? No reason is given and then suddenly the scene shifts, as Jesus empties the Temple, which too was not ready for his visit:

"When he came back into Jerusalem, Jesus entered the Temple courts and began driving out those who were buying and selling there. He overturned the tables of the money changers and the benches of those selling doves, and would not allow anyone to carry merchandise through the Temple courts. And he taught them: “Is it not written: ‘My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations’? But you have made it ‘a den of thieves.’” (11.15-17)

Suddenly, danger flashes, hatred mixed with fear:

"The chief priests and the teachers of the law heard this and began looking for a way to kill him, for they feared him, because the whole crowd was amazed at his teaching. (11.18)

But this scene too ends indecisively, as if nothing has happened:

"When evening came, Jesus and his disciples went out of the city. (11.19)

That Jesus has left the city a second time seems mainly a set-up for Part Two of the tale of the fig tree:

"In the morning, as they went along, they saw the fig tree withered from the roots. Peter remembered and said to Jesus, “Rabbi, look! The fig tree you cursed has withered!” (11.20-21)

Jesus withers the fig tree even as he empties the Temple. Perhaps Mark thinks that this pairing is a sign that Jesus is finished with the Temple too, since he finds it bereft of prayer just as a barren tree is bereft of fruit. He may be after something else, and so the scene switches suddenly to a teaching on faith that pushes things still farther:

"Have faith in God. Truly I tell you, if anyone says to this mountain, ‘Go, throw yourself into the sea,’ and does not doubt in their heart but believes that what they say will happen, it will be done for them. (11.22-23)

Which mountain gets thrown into the sea? Perhaps the Temple Mount itself? Faith now set against this holy mountain? If that is what Mark has in mind, no wonder that the people are confused and the leaders outraged: by the logic of Jesus’ words, the Temple is put aside by faith — as if a mountain plunged into the sea, as if withered like a fig tree, neither was ready for the Lord at his arrival.

To close the scene, lest there be only these hints of endings and destruction, Jesus speaks of real prayer, simply and effective, words from the heart spoken right to God, words of hope and forgiveness that do can be uttered anywhere:

"Therefore I tell you, whatever you ask for in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours. And when you stand praying, if you hold anything against anyone, forgive them, so that your Father in heaven may forgive you your sins. (11.24-25)

But perhaps these consoling words, spoken right at this point, make things worse. Visit Jerusalem and the Temple — and then leave them behind. Cease to be patient with those who profess piety and faith but do not actually have faith, do not actually pray. Instead, pray right where you can pray, just when you need to pray — and that is enough. Go directly to God, wait no longer on those who promise fruits but give none. No wonder they are annoyed and upset.

By this logic, it seems that Jesus may have terrified them all, impatient with the establishment and urging people to go straight to God in their times of need. Can’t have that, can we? We too should be terrified: Jesus is changing everything. We may be tempted to put a stop to it, we think — and so the rest of this very sad week gets under way, ending on Calvary. (Easter still only a promise, over the horizon.)

By this logic, it seems that Jesus may have terrified them all, impatient with the establishment and urging people to go straight to God in their times of need. Can’t have that, can we? We too should be terrified: Jesus is changing everything. We may be tempted to put a stop to it, we think — and so the rest of this very sad week gets under way, ending on Calvary. (Easter still only a promise, over the horizon.)

All of this is conjecture, of course, but even so, we are still stuck with Pilate’s question, “Why crucify him? What crime has he committed?” Let us take some time this Holy Week to think anew about what happened in Jerusalem those last days, making Pilate’s tormented question a real question for us right now, in Holy Week 2021. We want peace and we yearn for the joy of Easter, but first let us try to restore uncertainty, fear, and doubt to this hoy week that ends in death. It may be that we cannot really appreciate what is means to be with Jesus, to love him with an overflowing, endless love, if we cannot appreciate why he might also terrify us — all things made deeply, frighteningly new! — even to the point that we might be tempted to banish him from our lives.

(This reflection is in part indebted to an article by Paul Brooks Duff, “The March of the Divine Warrior and the Advent of the Greco-Roman King” [Journal of Biblical Literature, 1998])

Comment: I am acutely mindful that this reflection is a hard one, particularly as Palm Sunday this year falls on the first full day of Passover. Nothing said here, and nothing that Mark wrote, should in any way make us have less gratitude and deep love for the Jewish people, their enduring faith and brave witness over many centuries. Mark is talking not about “them” but about us, you and me.