"Now Thomas (known also as the Twin), one of the Twelve, was not with the disciples when Jesus came. So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord!” But he said to them, “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

"Now Thomas (known also as the Twin), one of the Twelve, was not with the disciples when Jesus came. So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord!” But he said to them, “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

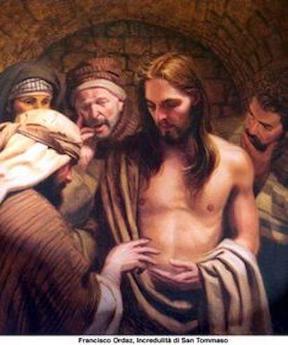

"A week later his disciples were in the house again, and this time Thomas was with them. Though the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you!” Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.”

"Thomas said to him, “My Lord and my God!” Then Jesus told him, “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.” (John 20.24-29)

Poor Thomas. He wanted to see Jesus; he would not believe simply because his fellow disciples told him that they had seen him. Blessed are we if we believe without seeing is the first message we receive from this Gospel, and a good enough sermon might end there. But there is more: Thomas actually wanted not only to see Jesus, he wanted to touch Jesus intimately, putting his finger in the nail holes and his hand into the side of Jesus: not just as proof, I think, but also a way to reconnect with the Jesus who died and has now returned. Jesus says, Go ahead, do it, and perhaps he is not merely scolding Thomas, but inviting his touch. (Whether he actually does so, John does not say.)

Touching was already on the mind of the Gospel writers as they recounted the Resurrection events. Earlier in John 20, Jesus had said to Mary,

"Do not touch me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father. (20.17)

Had she tried to embrace him? We do not know, yet he seemed in a way to be leaving here, leaving her. Yet soon after that, when Jesus first visits the disciples in the absence of Thomas, he displays the very wounds that Thomas wants to touch:

"After he said this, he showed them his hands and side. The disciples were overjoyed when they saw the Lord. (20.20)

In Luke's parallel account, Jesus explicitly invites physical contact:

"They were startled and frightened, thinking they had seen a ghost. He said to them, “Why are you troubled, and why do doubts rise in your minds? Look at my hands and my feet. It is I myself! Touch me and see; a ghost does not have flesh and bones, as you see I have.” When he had said this, he showed them his hands and feet." (Luke 24.37-40)

Did they touch him? It would seem so — why not? Seeing — and then touching, for a more intimate experience of the risen Christ.

In today’s confrontative scene, Jesus seems then to be taking Thomas seriously, offering Thomas the chance to do precisely what he was asking for:

"Put your finger here. Look, see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe. (20.27)

When Thomas wanted contact more intimate than words and vision, he was unknowingly standing at the start of a long tradition that focused on the wounds of Christ. As we all know, on Mount Alverna, intimately close to the presence of the radiant crucified Lord, St. Francis of Assisi famously received the stigmata, the marks of the nails in his hands and feet, a long gash in his side. Vividly too (as I learned in the course of reading her with my students last week) in her famed Herald of Divine Love Gertrude of Helfta, a learned cloistered nun writing at the start of the 13th century, seems to have received interior, spiritual stigmata as a gift from Christ. But even more, she envisioned Christ as taking her hand and placing it in the wound in his side, a sign sealing their commitment to one another:

"And immediately (in my nothingness) I saw you opening with both hands the wound in your deified heart, the Tabernacle of divine faithfulness and infallible truth. You commanded me to put my right hand into the wound. Then, contracting the opening of the wound in which my hand was now enclosed, you said: “See, I promise to keep intact the gifts which I have given you.” (Herald of Divine Love 2.20)

And so on, a few mystics in every century, touched by Christ, touch him and in remarkable ways share in his wounds.

And so on, a few mystics in every century, touched by Christ, touch him and in remarkable ways share in his wounds.

But we are not medieval mystics, so what does this mean for us now, this interplay of hearing and seeing but also touching the risen Christ? First, we can think about our spiritual lives, and the metaphors we use. Is hearing enough? Is it enough to see from a distance? Should we not also feel what we see and hear? What does it mean to experience the risen Christ?

Second, cherishing the wounds of the risen Christ can be a way to acknowledge and reverence our own wounds. Just this week Peter Wehner wrote for the New York Times a remarkable meditation on the wounds that remain visible even in the risen Christ, and in us too, even as we regain life and hope and love:

"I find the concept that fractures in our lives can be redeemed and leveraged for good deeply moving. All things, even broken things, can be made new again, and sometimes they can be made even more beautiful. And they need not be hidden, in shadows or in shame. None of this means that people, if they had a choice, would endure the blast furnace of pain and loss, of trauma and shattered lives. It means only that even out of ashes beauty can emerge.

After our pandemic year, families shattered by untimely deaths, careers and studies put on hold, jobs lost, lives scarred in quiet ways: as survivors in small and large ways, we are invited also to an intimacy with Christ who is eternally marked by the suffering of his crucifixion, like him marked by the things that happen to us. We do this by a simple, honest acceptance of our lives, scarred by our own history and choices, by our sins and mistakes: marred and imperfect bodies — on which the death and resurrection of Christ are recorded, as if written in a holy book. He is risen, and we, touching his wounds as Thomas wanted to do, are enabled to be in touch with who we are, however scarred we may be.

And finally, we can turn a compassionate eye to the suffering around us. In 2013, Francis spoke this way on July 3, the feast of St. Thomas:

And finally, we can turn a compassionate eye to the suffering around us. In 2013, Francis spoke this way on July 3, the feast of St. Thomas:

"How can I find the wounds of Jesus today? I cannot see them as Thomas saw them. I find them in doing works of mercy, in giving to the body—to the body and to the soul, but I stress the body—of your injured brethren, for they are hungry, thirsty, naked, humiliated, slaves, in prison, in hospital. These are the wounds of Jesus in our day. (Pope Francis, July, 2013)

Just this March he again reminded us that there is no lack of wounds around us, and every wound is a wound of Christ:

"It is more than ever important in our day that Christ’s faithful people give witness to tenderness and compassion. Listening to the cry of the poor that resonates within us, allowing ourselves to be overwhelmed by the suffering of others and deciding to go out of our way to touch their wounds — which are the wounds of Christ — not only participates in the building of a better world, more a family, more evangelical, but it strengthens the Church in her mission to hasten the building of the Kingdom of God. (Pope Francis, in an address to Fidesco, a charitable organization)

The challenge, of course, is to take up this invitation, as much as we can, not only in the shadow of the cross, but also in light of the Resurrection: our role as witnesses, compassionately present as we can be, is to bring the hope of new life to people, even amid the wounds that scar their everyday lives.

And so Thomas, though a doubter — and as a doubter — actually got it right: to hear, to see, but also to touch the risen Christ gets us very deep into the meaning of the Resurrection.