As my contribution to the celebration of Laurel Ulrich’s career, I should like to evoke the site that in 1995 brought us together to begin a fruitful collaboration in teaching, exhibition curating, and publishing. I propose to take readers on a journey in both space and time.

The year is 1881. The purpose of our journey is to witness the event that marks the founding of what would become a historic house museum in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts. We take what use to be called “the cars” on the Boston & Albany Railroad to Worcester, where we transfer to a stagecoach that brings us to the small town of Shrewsbury. We are forty miles as the crow flies from Boston. We walk down the old Boston Post Road to find the handsome clapboard building with two front doors: the Ward Homestead.

The Ward Homestead,1720, enlarged in 1784-85; now the General Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, (photo: author)

Nahum Ward built the original house in 1720, just three years after the town was settled. His son, Artemas—of whom more below—was born in 1727, moved into the house in 1763, and lived there until his death in 1800. Artemas Ward finished enlarging the building in 1785 to accommodate the family of his son, Thomas Walter Ward, beside his own household. This is why there are two front doors.

Left to right: Sarah Henshaw Ward Putnam, Thomas Walter Ward II, Elizabeth Ward, Harriet Ward, General Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

Nearly a hundred years later, at the time of our visit, Thomas Walter Ward’s namesake son occupies the house with his two middle-aged unmarried daughters, Elizabeth and Harriet, and his widowed sister, Sarah Putnam. Sarah had returned to Shrewsbury from Marietta, Ohio in 1825, following the death of her husband just three months after their wedding. Her father, Thomas Walter Ward, Sr, bequeathed her “respectable house room” on his death in 1835.

The family income derived largely from the farmland associated with the homestead. Thomas Walter Ward, II had been a promoter of agricultural improvement. One aspect of his capital-intensive development of the farm had been the creation of the largest cattle barn of its kind in New England in 1848. By 1881, the date of our visit, the farm is in decline. But Thomas Walter Ward, II, who turns 83 in in 1881, and who would live for another nine years, was a proud yet sorrowful man. He was proud not only because his father, the first Thomas Walter Ward, had been sheriff of Worcester County, but because his grandfather, Artemas Ward, had been a hero of the Revolutionary War. We can see him in old age, seated in the parlor near the 1795 portrait by Raphaelle Peale of Artemas Ward.

Thomas Walter Ward, II seated near Raphaelle Peale’s portrait of his grandfather,

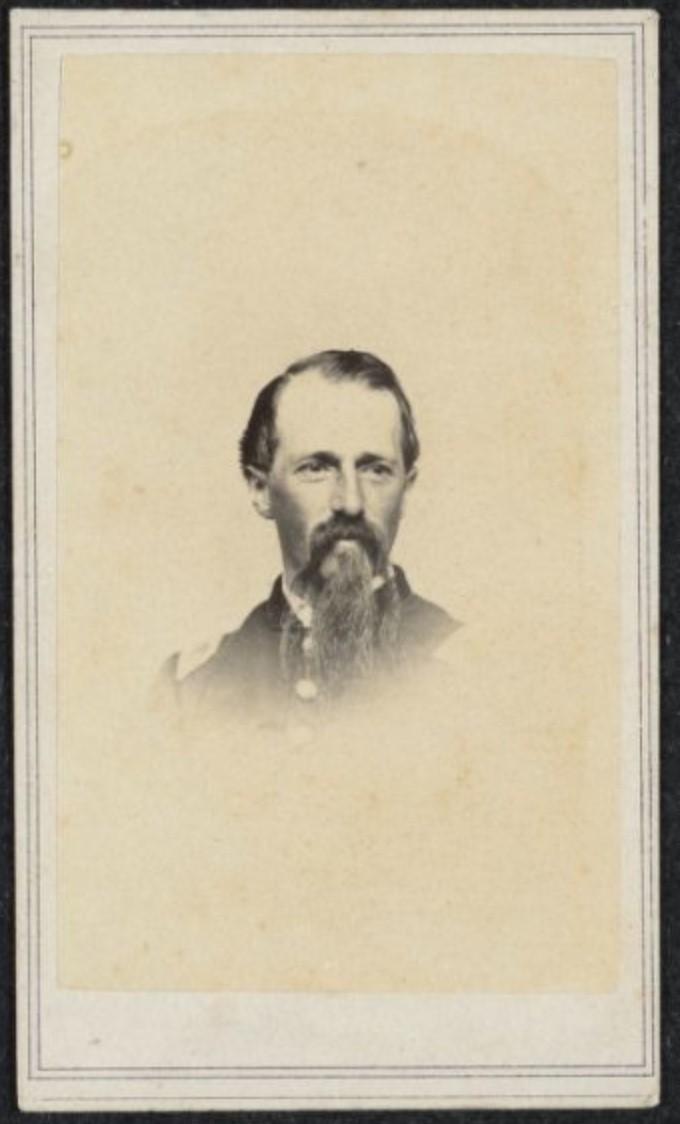

Maj. Gen. Artemas Ward (unidentified photographer),

General Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

As a brigadier general of militia, Artemas Ward had been the senior officer of the Patriot forces during the siege of Boston soon after the outbreak of hostilities in April, 1775. He was superseded by George Washington, but, promoted to major general, was second only to Washington in seniority. He was a member of the Continental Congress, and served in Congress as a US representative for Massachusetts between 1791 and 1795. He also had a distinguished judicial career. General Artemas Ward’s renown—now almost entirely faded—is the reason for our visit to the Ward homestead.

We are not the only ones to throng the Boston Post Road in front of the Ward Homestead early on the morning of September 8, 1881. Two days later, on September 10, Elizabeth Ward, the elder of Thomas Walter Ward’s unmarried daughters, would write a letter to her sister-in-law, Clarinda Clary Ward, describing what had happened. Clarinda was the wife of Elizabeth’s elder brother, Thomas Walter Ward, III. After the Civil War, they had homesteaded in Nebraska. Elizabeth Ward takes up the story.

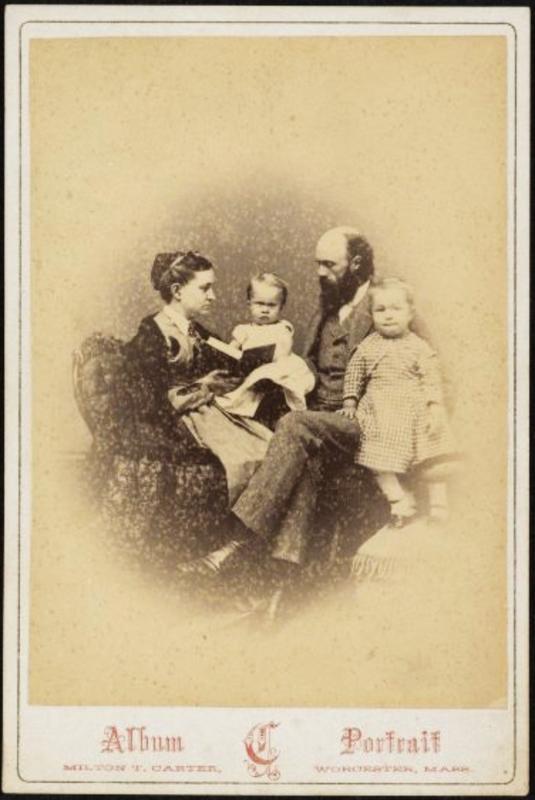

Thomas Walter Ward, III, Clarinda Ward, and their two sons,

by Milton T. Carter, 1867 (?),

General Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

My dear Sister,

While the events of the last few days are fresh in mind, I will attempt to tell you of some

which I am sure will not be uninteresting to you. As I wrote you, we were expecting a glimpse of the Hero who “marched to the sea” [General William Tecumseh Sherman] and desired to make the most of the five minutes which Senator Hoar [U.S. Senator George Frisbie Hoar] promised us. So we had Gen. Ward’s desk brought down stairs into the room in which he died, put some ink into the silver ink stand he once was accustomed to use, and placed one of his chairs nearby for the present commander in chief to sit and write his name. We decorated the rooms with flowers and the portrait of our great grand sire with the stars & stripes, had the old dining table of his spread and filled with cake fruit and lemonade for drink, opened the front-doors with brightened knockers and, ourselves arrayed I hope appropriately, we sat down to wait at half past nine Thursday morning.

Interior of the General Artemas Ward House decorated for the visit of General William Tecumseh Sherman, 1881, unidentified photographer, Gen. Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

The star spangled banner was floating joyously over the roof top, and another fell in graceful folds over the entrance door. Up through the street flags were flying, and the people came out in masse to do honor to the occasion. Father had been invited by the Wor[cester] Reception committee to be at the cemetery and ride here with them, so he was there to receive them and after the speeches which you will see in the paper I send you, they drove down the hills and up to the Ward Mansion, Father in the first carriage on the seat with Gen. Sherman! And Samuel [Elizabeth’s elder brother] with them. They entered the house first and Father introduced him to us separately, I should have said that Aunt Putnam and Samuel’s family were here and helped us receive. Then the others entered, and, after being introduced to the portrait, the General was missing for a minute or two, and I found he and some others had wandered through the kitchen and back room, and I next saw him at the well! Father said to him “I am going to sink the bucket and I want you to draw it up.” “No” said the Gen[eral]. “I am going to put it down myself,” and he did to the length of the rope and then took a good drink saying “that is water”! Then he was told he must leave his autograph and was conducted to the writing desk where he was so much interested in a few relics, the orderly book particularly, that the chief martial [sic] who had the ordering of the affair was obliged to say several times “General our time is up” before he would leave the chair. On saying good bye to me he said he would want to come again if ever he came into the region, “but I live in St. Louis. How can anybody get here? What do you live away off here for?”! and then after the adieux were said they drove away and it was all over, all “over in half an hour!” Mr. Hoar said to me that it was the pleasantest occurrence of the Gen[eral]’s visit, their trip to Shrewsbury. When the “banquet hall deserted” feelings began to steal over us, we set ourselves to work. I gathered up the fragments of cake and sent Hat [Harriet] of[f] to rest, for she was going to the Fair in the afternoon with Samuel & the girls.

Elizabeth Denny Ward Baldwin, by C.R.B. Claflin, 1875,

General Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, MA

Soon after the stage drove up and there was Aunt Baldwin come to see the General! [Elizabeth Baldwin: Thomas Walter Ward, II’s elder sister.] I never saw a more disappointed person in my life; one plan had been for the party to come in the P.M. That was fixed in her mind and she would not believe the morning paper that said they would start at half past eight—so here she was, and could hardly be persuaded to take off her bonnet, but was going right back in the next stage! She was excited and tired and we all said she must not go, so after a while she consented to stay and have some dinner after which a good nap refreshed her and she became somewhat reconciled to the situation. [A]fter H[arriet] returned in the evening the national colors were taken in and we were ordinary people again, but with another pleasant memory added to those that cling around the old Shrewsbury house…[i]

Thomas Walter Ward, II (standing) with his siblings, Elizabeth Denny Ward Baldwin (“Aunt Baldwin”), Sarah Henshaw Ward Putnam (“Aunt Putnam”), and Henry Dana Ward, unidentified photographer, c. 1885, Gen. Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

Clearly, Elizabeth Ward had great talent as a writer, which she would put to good use in her history of her home town, published in 1892 as Old Times in Shrewsbury.[ii] More especially pertinent to my purpose in recounting this visit in 1881, Elizabeth and her sister Harriet devoted themselves to collecting and preserving the material traces of their great grandfather, General Ward, and his descendants. They assiduously collected not only memorabilia of the General but those of their forbears who followed him. Among them is a broken Staffordshire plate decorated with a transfer print of New York City Hall. The plate is part of a set called “The Beauties of America,” and had probably been acquired by Thomas Walter Ward, II and Harriet Grosvenor, as a wedding gift in 1825. Instead of discarding the shards, their daughter, Harriet, carefully preserved them, and affixed a note: “To be soaked apart and put together by someone who has more patience than Harriet Ward.” All things associated with the family’s past—documents and material items, however damaged—were to be preserved, and Harriet wrote herself into the record of preservation and recollection.

J. & W. Ridgway, Hanley, Staffordshire, England, semi-vitrified earthenware with transfer print decoration, c. 1825,

General Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

Elizabeth and Harriet continued to gather materials in the house for the rest of their lives. Elizabeth died in 1900, and her younger sister, Harriet in 1909. Their nieces, Ella, Clara, and Florence Ward, became caretakers. Their cousin, Artemas Ward, who was a successful advertising company owner in New York, came to the financial rescue of the property. On his death in 1925, he bequeathed it to Harvard University to be what he termed in his will “a public and patriotic museum” dedicated to the memory of General Artemas Ward.

For many decades, although the fabric was well maintained, and the house opened for public visits, it languished in any museological sense. In 1996, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and I were invited by the university to propose ways in which the house and collection could be revivified, most especially within the research agenda and curriculum of the university. Our foremost recommendation was that a professional curator should be appointed who could take on the various scholarly and practical tasks associated with running any museum. This was done, and, under curator, Paula Lupton, the house and its contents now receive meticulous care, including the documentation, digitization, and conservation of the collections.

Laurel and I used the Ward House and its contents as our object of study in two successive seminars in 2005 and 2006. We and our students researched things within the house. Together, we produced a great deal of original work that found public as well as scholarly expression in the exhibition that Laurel and I curated at the Harvard Art Museums in 2006-7.[iii] Our research on the Ward House was a vital constituent in the work that Laurel and I have produced individually and in collaboration on the use of tangible things for historical purposes. This led to our graduate seminar in 2010, our General Education course and exhibition, “Tangible Things,” in 2011, and culminated in our 2015 book, Tangible Things: Making History through Objects, written with Sara Schechner and Sarah Anne Carter, with photographs by Samantha van Gerbig.[iv] But this aspect of disciplinary formation in History—appealing to tangible things—goes back to the visit we have made together today to witness William Tecumseh Sherman paying his respects to his predecessor as the most senior US army officer, Artemas Ward, at Ward’s house in Shrewsbury. For it was this visit, in prospect, that impelled the sisters, Elizabeth and Harriet Ward, to refashion the house in a way that would later characterize the conventions of a house museum. It encouraged them to gather family memorabilia for the “Hero who marched to the sea” to inspect, and, as we have seen in Elizabeth’s account of his visit, inspect them he did.

Charles Grosvenor Ward, 24th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, killed at the Second Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, 1864,

Gen. Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

Although Sherman’s attention was directed towards the portrait and effects of his predecessor in the War of Independence, Elizabeth and Harriet Ward ensured that there were reminders of the dreadful conflict in which he had played so conspicuous a role between 1861 and 1865. I mentioned that Thomas Walter Ward, II was both proud—proud of his lineage—and sad. Of his two sons who went to war as Union officers, only one, Thomas Walter Ward, III, returned. The elder, Charles Grosvenor Ward, a lieutenant in the 24th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, was killed in May, 1864 at the Second Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia. His father paid for the return of his effects, and Paula Lupton, curator of the Ward House Museum, discovered his saddle and saddle blanket, marked with his regimental insignia, in the barn.

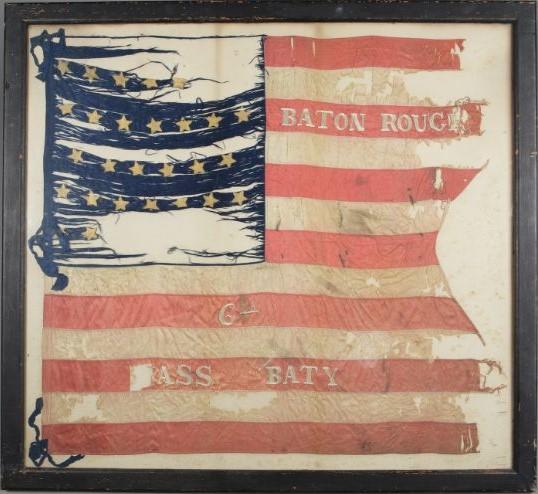

Guidon of the 6th Battery Massachusetts Volunteer Light Artillery,

Gen. Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

A conspicuous Civil War relic in the house, likely acquired by Elizabeth and Harriet Ward from their first cousin, William Ward Carruth, probably with General Sherman’s visit in mind, is the guidon of the 6th Battery Massachusetts Volunteer Light Artillery, commanded by Lieutenant, later Captain, Carruth with distinction at the Battle of Baton Rouge in 1862.[v]

It is hardly surprising that the Wards should bring to the fore not only things associated with their forebear, Artemas Ward, but with the recent conflict that had inflicted such appalling losses on just about every community, north and south. The little town of Shrewsbury, population 1,558 in 1860, lost 29 of its menfolk in military service. Scarcely a family was unaffected.

I think we are justified in seeing the visit of William Tecumseh Sherman to the Ward homestead on September 8, 1881 as the moment of inception of what would become a “popular and patriotic museum” thanks, in the first place, to the efforts of Elizabeth and Harriet Ward. Their endeavors over the following twenty or so years conform with a far larger movement of the recollection of the colonial past through the preservation of buildings and their contents, stimulated, in particular, by the extensive centennial celebrations of the Declaration of Independence in 1876. This “colonial revival” has been much studied in recent years, and Laurel Ulrich’s contribution, The Age of Homespun, is among the most original and illuminating.[vi] For instance, in 1891, landscape architect Charles Eliot founded the Trustees of Reservations. In 1910, William Sumner Appleton founded the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, today’s Historic New England, which now operates 36 house museums. We consulted with both organizations when forming our recommendations for the future uses of the General Artemas Ward House Museum.

In terms of disciplinary formation, specifically History, although we have followed in the footsteps of James Deetz and others in mobilizing tangible things to make material culture history, the antecedents go back rather further.

Elizabeth and Harriet Ward, 1849, unidentified daguerreotypist, Gen. Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

In particular, I want to acknowledge Elizabeth and Harriet Ward, who focused not only on the great men among their forbears and contemporaries, but the women, too. I also want to acknowledge their widowed aunt, Sarah Putnam, to whom they were especially close.

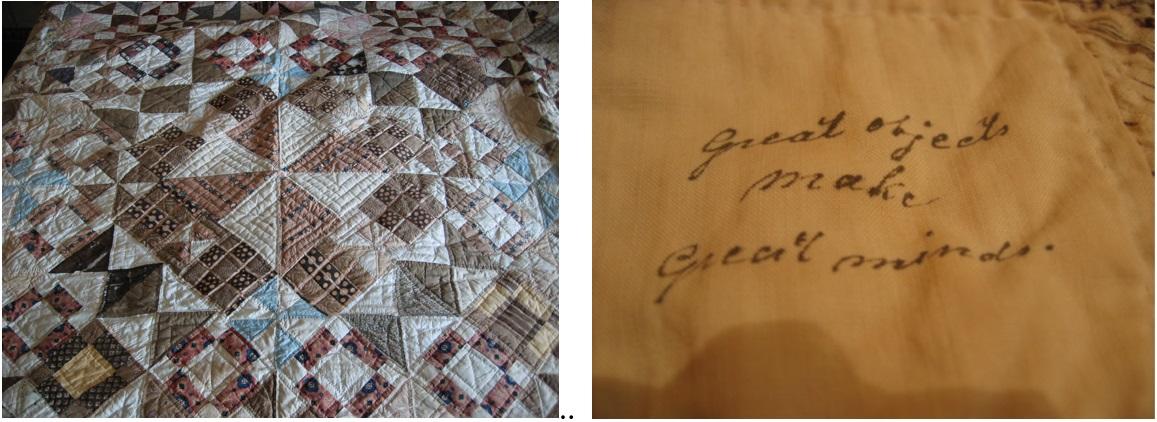

Sarah Henshaw Ward Putnam, Pieced Quilt with Inscriptions, 1881, and detail, “Great objects make great minds,” from Edward Young, Night-Thoughts on Life, Death & Immortality, 1742-45

Gen. Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts (photos: author)

In the same year in which General Sherman visited the Ward homestead, Sarah Putnam completed a quilt as a gift for her beloved nieces. It remains in the Ward House Museum, its inspirational text inscriptions penned on individual quilt squares. Sarah Putnam’s quilt prompts viewers now to take material things that are traces of the past as seriously as any other constituent of the historian’s craft, and viewing it brings our journey to Shrewsbury in 1881 to a suitable close.[vii]

Harvard University seminar “Confronting Objects/Interpreting Cultures” at the Gen. Artemas Ward Museum, Oct. 2010 (photo: Paula Lupton)

Ivan Gaskell is Professor of Material Culture at Bard Graduate Center in NYC, and faculty director of the focus project, co-author with Sara Schechner and Sarah Carter, and Laurel, of the 2018, Tangible Things book, exhibit, and course. Longtime co-teacher with Laurel during his tenure at Harvard. Curator. Editor. Author of endless excellent things. Each year he enjoys a two month fellowship each spring at the Advanced Study Instutute in Göttingen, Germany.

[i] MS and typescript transcription in the General Artemas Ward House Museum, Shrewsbury, Massachusetts.

[ii] Elizabeth Ward, Old Times in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts: Gleanings from History and Tradition (New York: McGeorge Printing Co., 1892).

[iii] Ivan Gaskell and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “A Public and Patriotic Museum”: Artworks and Artifacts from the General Artemas Ward House, exhibition catalogue (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 2006)

[iv] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Ivan Gaskell, Sara Schechner, and Sarah Anne Carter, with photographs by Samantha van Gerbig, Tangible Things: Making History through Objects (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[v] For a discussion of this guidon, see Ivan Gaskell, “History of Things,” in Debating New Approaches in History, edited by Marek Tamm and Peter Burke (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), pp. 217-232, 239-246.

[vi] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001).

[vii] My thanks go to Paula Lupton, curator of the General Artemas Ward House Museum, for making Elizabeth Ward's letter available, as well as the nineteenth-century photographs reproduced in this article. My greatest debt is to Laurel Thatcher Ulrich for many years of stimulating collaboration and friendship. I gave an earlier version of this paper at the workshop, Objects and the Formation of Disciplinary Knowledge in Universities and Beyond at the Lichtenberg-Kolleg: Advanced Study Institute of the Georg-August University, Göttingen, in 2018, and was able to revise it thanks to my permanent fellowship at the Kolleg. I gratefully acknowledge the hospitality of the director, Martin van Gelderen, and his colleagues.