Laurel talks with graduate students Candace Kanes and Judith Moyer at the quilting bee held in her honor before leaving the University of New Hampshire.

Laurel talks with graduate students Candace Kanes and Judith Moyer at the quilting bee held in her honor before leaving the University of New Hampshire.

Laurel prefaces her essay, “A Woman’s Work is Never Done“ in All God’s Critters Got a Place in the Choir with a humorous poem written by Cathy Richardson that she read at her ward Relief Society:

Sweep the house

Make the bread

Never grouse

Smile instead

Make a list

Check the time

Put the wash

Out on the line

Exercise, be tall, be thin

Never let the wrinkles win

Take twenty minutes

for yourself

that’s what the experts

say will help.[1]

Laurel follows the seemingly timeless poem with Maine midwife, Martha Ballard’s tired lament from the late eighteenth century: “A Woman’s work is never Done, as the Song says, and happy she whose strength holds out to the end of the race.”[2] Martha may have been thinking of a seventeenth-century English ballad based on an older proverb: “A man works from sun to sun, but a woman’s work is never done.”[3] Laurel might have been thinking of her own days, but instead, she tells the story of the wife of a Dover, New Hampshire minister.

Why do women’s days go on past sundown when men declare their work day done? Not just because we are compulsive doers juggling multiple tasks, Laurel suggests, but rather because women’s work is people oriented. Women’s work is “directed toward nurturing and sustaining others.”[4] In the case of the now famous midwife, Laurel explains, “Some part of Martha Ballard’s work, for example, was simply noting the welfare and whereabouts of others–her husband, sons, daughters, household helpers, and neighbors. As a consequence, her work spilled over into every cranny of her farm and town.”[5] Women could not confine that work to the hours “from sun to sun.” Laurel’s work while she was at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) was certainly not accomplished between sunrise and sunset.

Laurel moved to Durham, New Hampshire in the fall of 1970 when her husband Gael took a position in the Chemical Engineering Department at UNH and Laurel was finishing her MA in English at Simmons. An excerpt from Professor Charles Clark's book The Eastern Frontier in the UNH Magazine drew Laurel to history. The English Department wouldn't let her do a joint degree with History, so with Charlie's nudging, she switched to History. Laurel then taught as a half-time adjunct assistant professor in the Humanities Program. She was hired to teach Early American History at UNH in 1985, rising through the ranks to professor, before moving to Harvard in 1995. This narration makes it sound so fluid, so different from the lives most graduate students experience in our academic world in flux. It wasn’t. Laurel worked “from sun to sun,” mostly in ways that no one saw and that would not fit anywhere on a curriculum vitae handed to a promotion and tenure committee.

Historians illustrate complex truths best by telling stories. Certainly Laurel does. Let me tell this Harvard audience just one story from New Hampshire. For a few years, Laurel and I were the only women in the History Department at UNH. Need I add that we cross country skied, walked, ate ice cream, and talked together often? One of our very kind senior male colleagues was chairing the undergraduate committee on which we both happened to be serving. He resigned from our three-person committee suddenly in the middle of the semester. It was not long before the explanation came. We were plotting against him. It was a cabal, he charged. Now to say that there was probably nothing more significant at stake on the Undergraduate Committee at that moment than setting a grade point for honors in major is not an exaggeration. That isn’t what we were discussing.

What had happened? It turns out, he had seen us, our heads together, as we walked down the hall and later apparently strategizing over lunch sitting outside under a shade tree on the lawn. Something must be up, he reasoned. It was, but not what he suspected. We were not discussing departmental policy. Instead, Laurel and I were team-teaching a graduate colloquium on Women and the Age of Revolution that semester. That alone should have been enough reason to chat. Unlike our senior male colleagues, we didn’t discuss seated in our offices, or over coffee around the seminar table. We rarely sat still, even in our offices. We talked while we walked in search of ice cream or cross country skied in the college woods near Laurel’s house.

In fact, our senior colleague was right. Not only were we not talking about grade point requirements or what to assign to our class. Instead, we were discussing logistics. The afternoons when our colloquium met were complicated affairs. Those logistics, while certainly not unchanging or timeless, fit the pattern Laurel described of work “that spilled over into every cranny of town, if not farm.” We taught the colloquium late in the afternoon, so that public school teachers working on continuing education credits or masters degrees could participate. That meant we both had children who needed minding.

In arrangements that will sound familiar to many of you, I picked up Laurel’s almost teenaged daughter Amy from her cello lesson somewhere in Durham while Laurel taught another class. Amy and I then drove to Little People’s Center where we retrieved my son David, a toddler, because the day care center would close before our colloquium finished. Three-year-olds are even more in need of transportation and care than cello-wielding almost-teens.

The three of us proceeded to Laurel’s house where I dropped David and Amy off for snacks and playing on their amazing tree swing. Gael had gotten home by then and he supervised Amy babysitting David. I returned to the History Department where Laurel had finished teaching another class, and together we led the two-hour seminar. At six, Laurel and I drove back to her house to free Amy to do her homework and thus to relieve Gael from child minding. I drove David home, thinking about what I would rustle up for dinner for my family as Laurel did the same. Those logistics were carefully calibrated and required coordination, hence our conversations that precipitated the resignation of the agitated committee chair.

Those team-taught colloquia were memorable. I remember our discussions with the graduate students about writing articles. Laurel and I each brought the drafts we happened to be writing at the moment. Laurel explained how she labored, word by word, crafting phrases. A few sentences could be a good day’s work. I showed my sheaves of paper, the ten drafts that I churned out, one complete draft a day until I had honed the prose to my satisfaction or the deadline. Of course, Laurel’s Midwife’s Tale had won or would win the Pulitzer, so which model would you follow if you were a graduate student? I don’t remember if we ever talked with the students about the childcare scheme that made it possible for us to sit at the seminar table discussing the writing process. We just took it for granted that this was the way women worked.

If not in the unceasing nature of her work, in what she accomplished while she worked, Laurel was a pioneer at UNH, whether writing books, leading protests of the faculty union, or guiding students to appreciate material objects. In her essay, “A Pioneer is not a Woman who Makes Her Own Soap,” she reflects on her heritage as the great-granddaughter of a pioneer to the Great Basin. Even though I wouldn’t be surprised if Laurel has tried making her own soap–I know she makes her own soup–Laurel acknowledges, “there are other dimensions to our pioneering. We have usually thought of the ‘frontier’ as an empty place beyond white settlement, a desert or prairie to be cultivated and civilized. But,” she adds, “A frontier is not a geographical space but a social space, an environment in which two different cultures meet and interact.”[6] Laurel, in that sense of introducing a new culture, or bringing different cultures into contact with each other, was a true pioneer. Our department changed in the decade that Laurel taught at UNH.

I remember when we hired our third woman to the history faculty. The reception was scheduled at Laurel’s house, in the living room warmed by a fire, looking out over Gael’s gardens and the tree swing. We were sitting in a circle, some of us on the floor because my daughter Marta was cruising around the company, probably presenting bits of cracker or a book to read to anyone who made eye contact. How could Lucy Salyer have even considered going somewhere else?

Laurel, Janet, and Marta with the completed quilt honoring Laurel's contributions to the University of New Hampshire.

Laurel, Janet, and Marta with the completed quilt honoring Laurel's contributions to the University of New Hampshire.

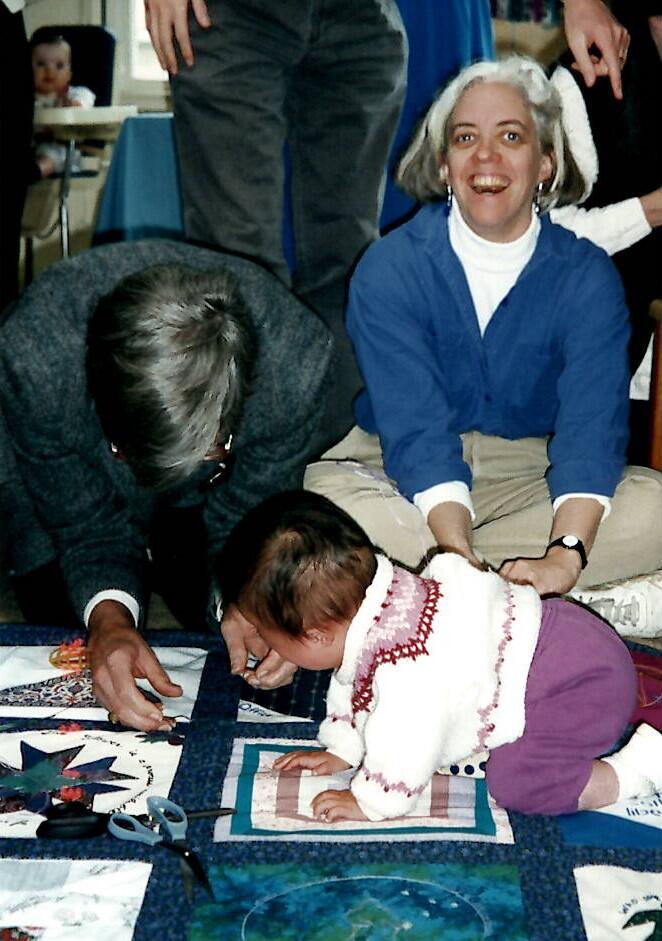

The change in culture was perhaps best summed up in the quilt that faculty, staff, and graduate students fabricated in her honor before Laurel left for Harvard. We stitched our squares with their wreathes, pockets, stars, an AAUP banner, ships and a skier into a quilt in the kitchen of my house as babies crawled between parents wielding needles and thread, with a Little Tykes basketball hoop overhead.

In her most recent book, A House full of Females, Laurel pictures the quilters of the Fourteenth Ward. “There is nothing peculiarly ‘Mormon’ about flowers, bees, baskets of fruit, eagles, or a mariner’s compass. Yet, brought together in a quilt made in Utah in 1857, these seemingly innocuous motifs carried a political charge.” Their politics comes from the combination. Laurel continues, musing: “There is an earnest, almost defiant cheerfulness about the quilt.” She finds the same attitude in the letters written by the Salt Lake women, “I can hardly wait until next week I want to put in seed in the garden, so bad,” Bathsheba Smith wrote George. They were always busy, or as Laurel puts it, “Relentlessly productive.”[7] There is always something more to do. This defiantly cheerful collegiality is a legacy Laurel left us up in our northern woods of New Hampshire.

Quilting for Laurel.

Quilting for Laurel.

Janet Polasky

Presidential Professor of History

[1]Cathy Richardson quoted by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “A Woman’s Work is Never Done,” in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and Emma Lou Thayne, All God’s Critters Got a Place in the Choir (Salt Lake City, Utah: Aspen Books, 1995), 110.

[2]Martha Ballard quoted by Ulrich, “A Woman’s Work is Never Done,” 111.

[3]Cited by Ulrich, “A Woman’s Work is Never Done,” 111

[4]Ulrich, “A Woman’s Work is Never Done,” 112.

[5]Ulrich, “A Woman’s Work is Never Done,” 113.

[6]“A Pioneer is not a Woman who Makes Her Own Soap,” in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and Emma Lou Thayne, All God’s Critters Got a Place in the Choir (Salt Lake City, Utah: Aspen Books, 1995), 91.

[7]Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A House Full of Females. Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835-1870 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017), 343, and 346. A discussion of the next phrase, “Relentlessly productive, but never good enough” will have to wait for another discussion.